News about or from Iran that appear in the Western public information domain are usually in connection with some disturbing political developments in the region, or international sanctions. Or both.

Or, like this year and especially in the recent months, hostile actions by foreign intelligence services and military against the Iranian regime.

Examples of these include the assassination of General Suleimani, a series of unexplained explosions at various strategic locations across the country, or more recently the assassination of Iran’s leading nuclear scientist.

The serious nature of these events frequently overshadows other news from the cyber space, such as alleged Iranian activities on the online disinformation front (examples here and here).

Iran and the Middle East in general remain a volatile region, with many international relations experts pointing out the possibility of the next global conflict starting there.

All of the above are the reasons why I thought it would be interesting to conduct some research of the Iranian online landscape.

1. Iran's ASN numbers

ASN stands for Autonomous System Number. Such numbers are global unique identifiers and are assigned to autonomous systems used by ISPs so that they can exchange routing information with other ISPs.

Iran is known for its strict censorship of the Internet, so it should be no surprise that every single one of the top ISPs is controlled by the government.

The top ISP in Iran, judging by the list of IP addresses, is the Iran Telecommunication Company PJS, currently with close to 3.5 million identified IP addresses, a large majority of which are IPv4.

Ping and connectivity tests that I carried out with sample IP addresses for this ISP suggest the connection speed is very poor,: on average it’s under 10Mb/s.

The second largest ISP, which by the way is reflective of the rapidly expanding mobile Internet market, is the Mobile Communication Company of Iran PLC. They control over 2 million IP addresses.

Surprisingly, mobile Internet is currently the most reliable and statistically the fastest in all of Iran, with average speeds of 20Mb/s.

The third largest ISP is the Information Technology Company, with close to 2 million IP addresses.

The fourth largest is the Iran Cell Service and Communication Company, also the second largest provider of mobile Internet services in the country. They control just over 1 million of IP addresses.

Naturally enough, the number of websites hosted by mobile Internet providers is significantly smaller than with their traditional broadband ISP counterparts.

The fifth largest ISP is the Aria Shatel Company Ltd, probably the most modern and Western-like Internet provider, with just above 1 million active IP addresses.

Overall, there are approximately 12.5 million of IP addresses, officially identified as belonging to Iran.

This figure is without doubt bigger as it does not include non-Iranian IPs, even if those are in long term use by Iranian entities.

Detailed statistics on Iranian ASN numbers can be found here.

Major IP address blocks for Iran are seen here.

IP address ranges and total counts identified here and here.

IPv6 stats for Iran here.

2. Iran's government websites

The most common domain used by the government is .gov.ir, but several websites just use the .ir top level alone (for example, the www.president.ir domain).

If unsure about these nuances, check out my post discussing domain level naming structure here.

The top level .ir domain is administered by the Institute for Research in Fundamental Sciences, located at the Shahid Bahonar (Niavaran) Square, Tehran 1954851167.

The Iranian government has 19 ministers, all in charge of a separate ministry; each of those has its own domain:

- Education – https://www.medu.ir/ – 217.218.26.200

- Communications and Information Technology – https://www.ict.gov.ir/ – 78.38.249.221

- Intelligence – http://www.vaja.ir – 2.187.252.17

- Economic Affairs and Finance – https://mefa.ir/ – 46.209.206.201

- Foreign Affairs – https://www.mfa.gov.ir/ – 185.143.233.5

- Health and Medical Education – https://behdasht.gov.ir/ – 185.123.209.86

- Cooperatives, Labour and Social Welfare – https://www.mcls.gov.ir/ – 185.192.112.3

- Agriculture Jihad – https://www.maj.ir/ – 79.175.135.30

- Justice – https://www.justice.ir/ – 62.193.12.10

- Defense Armed Forces Logistics – http://www.mod.ir/ (website not resolving, archived version available here)

- Roads and Urban Development – https://www.mrud.ir/ – 5.202.186.133

- Industry, Mine and Trade – http://www.mimt.gov.ir/ – 217.11.21.21

- Culture and Islamic Guidance – https://www.farhang.gov.ir/ – 78.157.60.190

- Interior – http://www.moi.ir/ – 185.143.233.5

- Science, Research and Technology – https://www.msrt.ir/ – 94.184.236.55

- Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts – https://www.mcth.ir/ – 91.99.102.190

- Oil – https://www.mop.ir/ – 217.174.16.48

- Energy – https://moe.gov.ir/ – 78.157.43.50

- Youth Affairs and Sports – http://www.msy.gov.ir/ (website not resolving, archived version available here)

There are thousands more government websites and it would not be practical to even try and enumerate more of them, but some of them can be detected by probing the IP addresseses I mentioned above (or other IPs residing on the same ranges).

Alternatively you can search for websites on the “.gov.ir” domain using some of the well known DNS tools or even Google queries, like this one (don’t forget to insert your own keywords of interest there!).

3. Iran's IoT landscape

One of the best tools for passive reconnaissance of the public facing / open infrastructure is Shodan.

This time around I was very eager to compare Shodan’s results to those presented by Zoomeye, but unfortunately this service has been consistently blocking my access to it whenever I tried to connect through a VPN (and connecting from your true residential IP address is not a safe option).

If you are not familiar with Shodan, there are still a couple of seats left on my Shodan, OSINT & IoT Devices online course – it’s a fully hands on, bullshit-free, practical intro to the Shodan platform.

The high level overview of all devices indexed by Shodan can be gleaned by using the country:ir filter – this offers nearly 2 million results which need to be narrowed down further.

You can probe specific known IP addresses, or you can expand the search filter parameters to search for devices in a particular city, like country:ir city:tehran or another Iranian city of interest (see the database of Iranian cities available here).

One of the most exciting features of Shodan is exploring open webcams and this can be done using the country:ir has_screenshot:true port:”80″ filter. It is important to focus on the specific port, as this will eliminate all results displaying static RDP login screens and similar results that yield limited information.

Some examples of the types of open webcams that you can find are seen below:

Footage from webcams (some of which you can actually log into without authentication) can be useful if you target a specific IP address that has an IoT device linked to it.

Also, even static screenshots can offer some background elements information – from objects on a desk, some of which might contain notes of interest, to signs, banners or names on a wall. All of this can be leveraged by zooming in close and applying visual identification.

I also had some successful results when scanning foreign language text from screenshots or static pages using free OCR apps, like ClipDrop that I discussed several weeks ago.

When it comes to probing previously identified IP addresses, you can find some pretty unexpected results.

For example, I extensively searched (and used up my daily Shodan search limit in the process!) for some IP addresses suspected to belong to a government IP address range.

Of the the IPs had an open webcam assigned to it, which seems to capture a backyard of what looks like a secure compound, with some national flags in it:

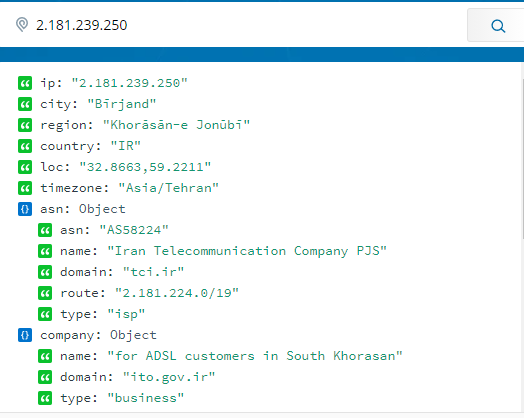

You can attempt an educated guess as to what this location is, but further information can be obtained by pivoting off the IP address (I used IPInfo.io):

The GPS coordinates 32.8663, 59.2211 bring us to a location marked on Google Maps as a park (Google Street View is not available in Iran), which does not add up, but looking for visual clues via Google’s trove of user uploaded photos we can sometimes get lucky and piece more information together.

It is also a good idea to search for distinctive land marks, buildings and terrain features that can be then cross-referenced using Google Maps satellite view.

More details on an IP address (and on the “neighbouring” IPs belonging to the same IP block) can be found on sites like this, while there are multiple other directions for exploring this angle further – such as employing other OSINT techniques to find an associated name, phone number, email, etc.

4. Iran's WiFi networks and device MAC addresses

WiFi reconnaissance is used primarily in penetration testing and ethical hacking, but in this case it can also be used to search for MAC (media access control) addresses of particular devices, if we have attributed such devices to a specific user.

For example, if an individual used a smartphone to carry out certain actions online (log into a platform, etc.) and left a MAC address identifier behind them, we can check if that MAC was at some stage in the past used for setting up a WiFi hotspot.

This is possible using Wigle, an access point mapping service, also commonly referred to as a war driving app.

War driving is an old WiFi vulnerability identification method, relying on moving around in a specific area while actively scanning for networks using a smartphone or a laptop configured to operate in “promiscuous mode”, as if it intended to find and connect to every nearby network.

War driving with Wigle is easy: all one needs is an Android phone with the Wigle app running on it. WiFi networks detected by a war driver will get recorded in the Wigle database, so that a record of historical data is present.

War driving was particularly useful during the early days of WiFi networks and it was mainly used to detect open, unprotected networks where anybody could connect up without any authentication.

Currently Wigle has information on over 700 million WiFi networks all over the world.

Broad searching on Wigle is very much possible, but as always, best results are obtained by narrowing down the search criteria. There are many parameters to define here, but to start off I like to define the country of interest and the date when a WiFi was last observed (YYYY-MM-DD format):

The results displayed contain information such as the SSID name, date ranges, level of encryption on the network, GPS coordinates and a handy map to visualize the location.

SSID names alone can yield a lot of clues, even though people nowadays tend not to name their WiFi networks using their surnames, like they used to do in the past.

You can also search by a specific address to see what networks are or were associated with it by Wigle in the past.

5. Iran's main state cyber actors

Iran remains a significant player among other countries with the anti-Western agenda. The Iranian cyber capabilities might not be on par with China or Russia, nevertheless Iran has been working towards improving their cyber offense through outsourcing their work to hacker groups both within and outside of the country.

I recall a conversation I once had during a cybersecurity conference with a senior military officer responsible for cyber defense. He likened Iran’s level of cyber warfare organisation to a messy server room, with cabling hanging in disarray from every rack and with equipment scattered chaotically in every corner. And yet, this is a fully functioning server room that gets the job done.

The military branch of the government with cyber offense capabilities is the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). The IRGC has many other responsibilities and cyber is only one of them. They oversee campaigns directed against both governmental and corporate targets globally. They are aided by several paramilitary, semi-professional militias like The Basij, who also formed their own cyber offense wing called the Basij Cyber Units (BCU).

Interestingly and somewhat unusually for an official military governmental organisation, the IRGC has been designated as a terrorist organisation by several countries, including the US.

The regime’s civilian intel wing of the government with cyber capabilities is the Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS). They conduct a wide variety of operations, from signals interception, Internet censorship, digital counter-intelligence and disinformation warfare.

In the wake of the infamous Stuxnet malware attack against Iranian nuclear research facilities, the regime created organisations like the National Passive Defense Organization (NPDO) and the Cyber Defense Command (styled on the US equivalent). Their objectives include protecting the country’s cyber infrastructure from attacks and conducting threat modelling, perhaps similar to the CSIRT bodies operating in Western countries.

Finally, Iranian cyber capabilities include companies and NGOs, such as the Mabna Institute (private tech and IT company located in Tehran, suspected of hacking activities on behalf of the regime) and The Nejat Society (NGO involved in online PR and propaganda efforts for the Iranian authorities).

6. Iran and social media

Iranian’s are very active on the global social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, Instagram or TikTok.

However, there are also several local social media sites whose popularity is unique to Iran.

To see the current trends, I would recommend starting with the Alexa Top Sites ranking, which shows the websites frequented the most in Iran.

Many of those sites are news platforms and those aren’t really useful for an OSINT investigator.

But here are some popular Iranian social media sites (yes, the Farsi language is a huge barrier):

- Aparat – an Iranian version of Youtube, works in a very similar way with video sharing and comments.

- Balatarin – link sharing website, dominated by political themes. Good for online handles searching.

- Cloob – a rather dated social media site that combines discussion forums and chat rooms.

- Digikala – online marketplace that looks and feels like eBay or Amazon.

- Divar – classified ads site, useful for searching usernames, but can be a hit and miss.

- Facenama – an Iranian clone of Facebook. Nowhere near close to the real thing in terms of usability.

- Sheypoor – classified ads site for mobile and desktop.

- Wisgoon – a photo sharing platform, clone of Instagram.

BONUS: Additional online resources on Iran

Here is a mix of some official and unofficial sources of information on Iran and Iran-related topics that have dominated the headlines in the past several years.

Reader beware: some of the content might present political bias or be slightly outdated, so do your own research before taking anything as gospel!

- The CIA World Factbook on Iran

- CIA reports and publications

- Global Firepower: Iran’s Military Strength (2020)

- Defense Intelligence Agency: Iran Military Power

- Arms Control Association – Iran Alerts

- The Iran Primer

- Institute For Science And International Security

- Iran Watch

- Recorded Future – Iran Hacker Hierarchy

- Small Wars Journal – Iran

- The Rand Blog – Iran

- United Against Nuclear Iran

- Iran Intelligence

- Iran Data Portal

- Parseek News

- Treadstone71 – Iranian Influence Operations

Matt thank you for this throve of OSINT.

عالی سپاس گزارم

ساختوساز کانتر

مطلب مفیدی بود ممنون

مواد غذایی و صنعتی

What interesting and excellent contract content. Thank you. Good luck